31.3.13

Going Over Old Times

Aunt Velma schooled us we should run in the field

when we got worked up, so as not to raise dust

in the house, which somehow managed always

to be just swept. So there we were,

playing at jousting, with Petey and Mort

on their invisible steeds they didn't want

to call just horses, holding branch lances

and going for each other like they hadn't

forgotten all the doublescrosses

they'd laid for each other in the past.

The dog and me were referee.

When everyone tired of knights we turned

to the day, like a grocer's thumb

on the earth. Even the trees which burst

out in yellow every so often

(you could smell "caution" on quiet days)

were grey, no buds, like spindly clouds.

I had a dog once looked like that,

the runt; he passed away unnoticed

almost, cause he was barely there

anyway. This was a runty day.

We fooled around the barn a good deal,

swinging on the rope from the rafters.

Mom brought it from Ohio where her Ma and Pa

used to tie it to the porch railing

in winter so you wouldn't get lost walking

from the house to the barn in a blizzard.

We all used it so we wouldn't stray

from the farm into the woods like we were tempted

to do on dumb days. Mom called it

"a headiness" that came over you in there,

so you'd walk for months without flagging,

and Percy and me knew it was the jays

who called you on and on from your home.

Even jays themselves have no home,

they've called each other away, following

those raggy cries up and down

from Salinas to Winnipeg. At any rate,

we kids stayed in the barn till suppertime.

And rain, which had been listening to the arguments

of gravity all the way down, hit

the drainpipe and said "Okay yessiree,"

agreeing to try the dry old earth for a spell.

We heard it during dessert, don't you know.

15.3.13

12.3.13

Seven Plots

The local community garden is just about ready for the year's first planting. I love the elements of these spaces before they get populated by flowers and vegetables. I gave these a painterly treatment to emphasize the blocks of color, texture, and shape. Otherwise they run the danger of looking like a bunch of snapshots of plywood and dirt, bricks and plastic.

10.3.13

9.3.13

Something There Is...

...that does not love a fence, to paraphrase Robert Frost. Here are three paths (of varying upkeep) in my neighborhood that one must go to a certain length to access. The last one is so popular as to have engendered a full-blown "path of desire."

7.3.13

6.3.13

Down to the Sea in Sepia Ships

Good lord, I'm sort of on topic for Sepia Saturday this week.

I had to memorize this seafaring poem and recite it in front of my 7th grade class. Drama! Never thought the day would come when I actually recalled the poem with fondness.

Approximately 48 weeks of the year my father taught days and nights, hosted TV and radio poetry shows (on which I often appeared, thinking nothing of this media exposure), hosted student and professional readings at the library, bookstores and the university, handled correspondence courses, edited Poetry Seattle and Seattle Review, and juried poetry contests for everything from the Pacific Northwest Writers' Conference to Mother's Cookies. He couldn't say no. Well, he said no to Mother's Cookies the second time around. In what few off hours were left he wound down after class in coffee houses and pizza joints with adoring students.

For all his civic and academic activity, he still was compelled to take a brief vacation every year, between summer and fall quarters. The family usually demanded it, even if he wanted to keep on teaching. This is when he typically allowed himself to get sick. He never took a sabbatical but taught for about 140 consecutive quarters. We typically went to the ocean. Even here—perhaps especially here—poetry remained foremost in his mind.

Although intensely, encyclopedically autobiographical, his poetry is still only a partial picture of the man. Take for example, an early poem, "Zero Tide."

|

| Westport, Washington 1957 - Pondering a new concept |

|

| Having pondered well |

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel's kick and the wind's song and the white sail's shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea's face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull's way and the whale's way, where the wind's like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick's over.

|

| Seadogs |

For all his civic and academic activity, he still was compelled to take a brief vacation every year, between summer and fall quarters. The family usually demanded it, even if he wanted to keep on teaching. This is when he typically allowed himself to get sick. He never took a sabbatical but taught for about 140 consecutive quarters. We typically went to the ocean. Even here—perhaps especially here—poetry remained foremost in his mind.

|

| On the ferry, 1959 |

I walked from our cabin into the wet dawn

To see the whitecaps modulating in,

The slow wash of the word in the beginning:

Wind on the bowing sedge seemed from Japan.

A cloud of sandpipers wavered above the dune,

Where surf spoke the permanence of sun.

Back inside, I sat on my son's bed

Where he sweetly slept, guarded by saints and poets,

Oceanic sunrise on his eyelids;

I whispered "Sean, get up! It's a clamming tide,"

And thought of chill sand fresh from lowering waters,

Foam-bubbled frets across the hard-packed ridges.

"Sean, it's a zero tide!" From a still second,

He came out of the covers like a hummingbird.

"Don't wake up Julian." In the ale blue light

He dressed in whirring silence, all intent.

Along the empty coast the combers hummed:

Sleepy gulls mewled in the clearing mist.

My wife and baby slept folded in singing calm,

Involuted by love as rose or shell.

|

| Sister ship ahoy |

|

| The old heave ho |

Now, what's missing from this poem, what the reader seeking to know the real Nelson Bentley can't know from this piece, is that it was I who was doing all the actual the dirty work. While I lay in the clammy sand, up to my armpit in pursuit of a razor clam, its slippery foot-tip in my fingers, shouting for assistance with increasing irritation, my father stood fifty feet away lost in the fog of his coalescing pentameter. He sort of came to, and sauntered over looking perplexed and distracted while the wily bivalve struggled from my grasp. I did manage to catch enough clams for chowder however, and he got his poem.

|

| On the sunny side of the boat |

|

| About ten years later... on Green Lake. From a sort of puff piece the Seattle Times did on Nelson in the late 1960s. |

(Portions of this post are lifted from the talk I delivered at the University of Washington Creative Writing Program's 50th Anniversary celebration, held at Seattle's Henry Art Gallery on May 27, 1997.)

4.3.13

Zoological

There's more (or sometimes less) to see at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoological Gardens than the fauna.

|

| Authentic guano collection signage at the penguin pool |

|

| Perhaps necessary because 90% of the animals actually in the exhibits are not in sight. |

|

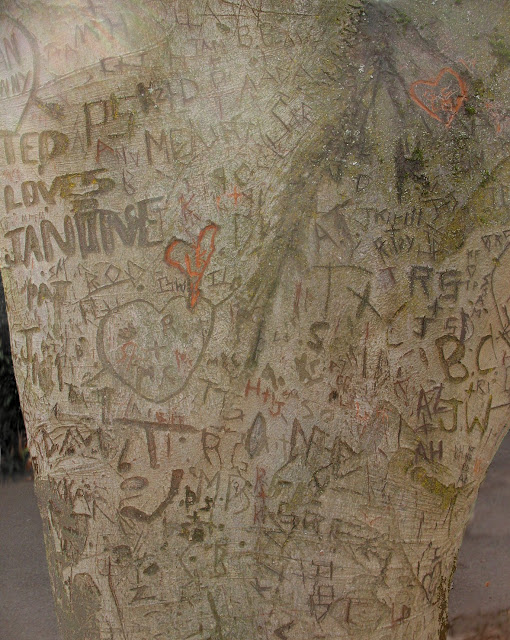

| No animals are in this exhibit either, just their names and initials. |

3.3.13

My Dear Watson

At last the sun came out on a weekend and I had some spare time to go shooting in the neighborhood. Here are three nearly monochromatic views of the grounds - literally - of the local elementary school where my wife Robin works. The playfield looks rather like a lunar landscape littered with mysterious hieroglyphics and artifacts.

What would an alien Sherlock make of such a landscape?

|

| Semi-festive hemi-bollards |

|

| The road to Espanol |

|

| The Western Hemisphere in danger of going down the drain |

What would an alien Sherlock make of such a landscape?

1.3.13

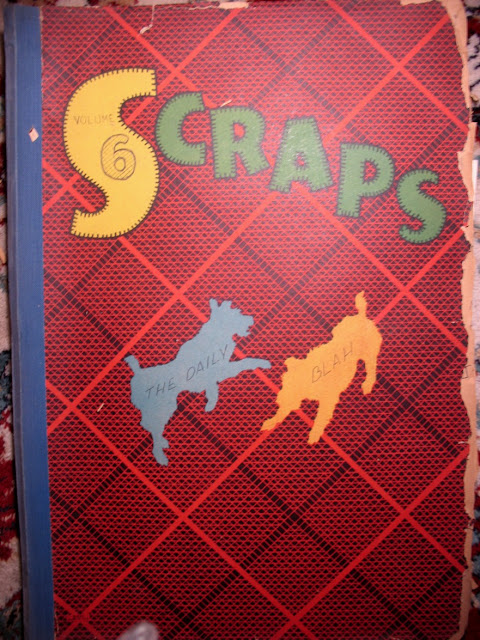

The Daily Blah, II

Presenting another installment of selections from the newspaper that my father Nelson Bentley produced during high school in the village of Elm, Michigan - now Livonia, west of Detroit.

The Blah not only served to recap of school events (primarily sports) but to highlight local news items and perhaps most importantly to provide an outlet for Nelson's developing raconteurship. I've blown these pages up for better reading, and you may need to scroll right for the whole text.

Here's a striking retelling of (a) Redford Union High basketball game, not to be outweighed by a conflagration at Nelson's Uncle Clyde's store. Nelson's dream was to become a radio sports announcer.

And here, inapropos to anything in surrounding pages, Nelson preserved, as a Daily Blah "rotogravure" section, a doodle made during his chemistry class. This shows his interest from an early age in classical poetry - Beowulf, in this case - an interest that wound up triumphing over sportscasting, as he eventually became an English professor.

The Blah not only served to recap of school events (primarily sports) but to highlight local news items and perhaps most importantly to provide an outlet for Nelson's developing raconteurship. I've blown these pages up for better reading, and you may need to scroll right for the whole text.

Nelson produced the following issue just before his 16th birthday. Both stories feature several of his friends and neighbors. I love the notion of collecting people's first memories.

Here's a striking retelling of (a) Redford Union High basketball game, not to be outweighed by a conflagration at Nelson's Uncle Clyde's store. Nelson's dream was to become a radio sports announcer.

The Blah featured many great character studies of the eccentrics who frequented Uncle Clyde's store, where Nelson worked, essentially unpaid, for many years.

And here, inapropos to anything in surrounding pages, Nelson preserved, as a Daily Blah "rotogravure" section, a doodle made during his chemistry class. This shows his interest from an early age in classical poetry - Beowulf, in this case - an interest that wound up triumphing over sportscasting, as he eventually became an English professor.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)